Although funding for these programmes was once restrained, both the Pentagon and Congress have increased support for their near-term deployment. The shift comes amid advances in Russia and China, which have conducted numerous successful tests and already fielded operational capabilities, raising concern over the strategic threat of hypersonic flight.

Experts remain divided on the implications of these systems for U.S. military advantage and global stability. Former Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Michael Griffin told Congress that the United States does not “have systems which can hold [China and Russia] at risk in a corresponding manner, and we don’t have defenses against [their] systems.” Despite this, the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 accelerated hypersonic weapons development, identifying them as a priority research and development area. Still, an operational U.S. system is not expected before 2027.

Unlike programmes in Russia and China, U.S. hypersonic weapons are being designed without nuclear payloads. This approach demands significantly greater accuracy and makes them more technically challenging to develop. As one expert observed, “a nuclear-armed glider would be effective if it were 10 or even 100 times less accurate [than a conventionally armed glider]” due to the destructive effects of nuclear blasts.

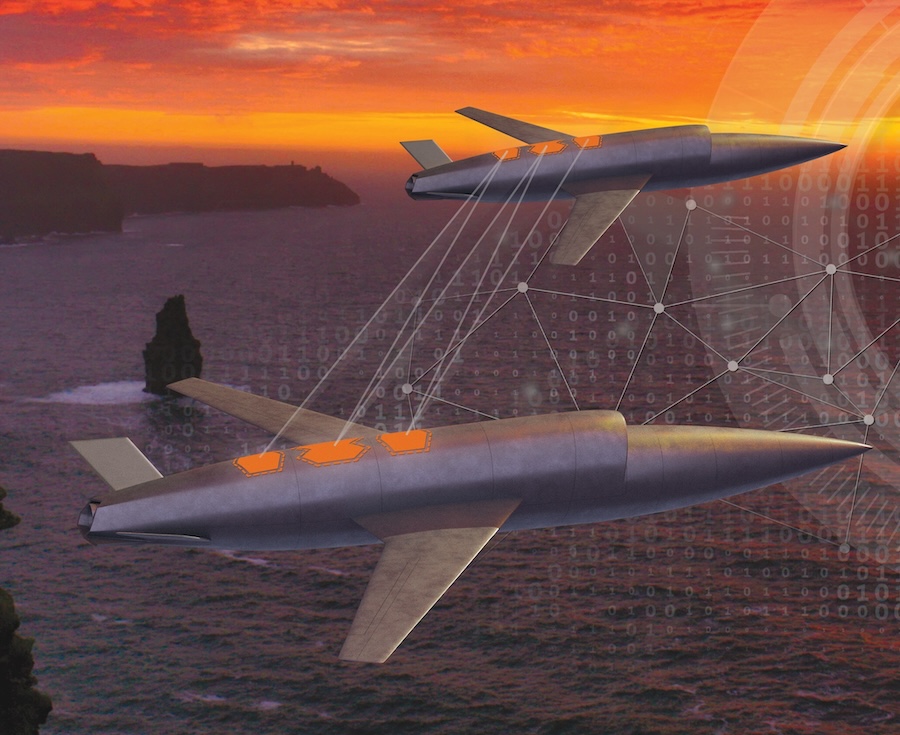

Hypersonic weapons, defined as flying at speeds of at least Mach 5, fall into two main categories: glide vehicles launched from rockets before gliding to a target, and cruise missiles powered by scramjet engines after acquiring their target. Unlike ballistic missiles, hypersonic systems do not follow predictable paths and can manoeuvre during flight, making detection and interception difficult.

Former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General John Hyten has explained that hypersonic weapons could enable “responsive, long-range, strike options against distant, defended, and/or time-critical threats [such as road-mobile missiles] when other forces are unavailable, denied access, or not preferred.” Because they rely on kinetic energy rather than explosives, conventional hypersonic weapons are designed to destroy unhardened or even underground facilities.

Their speed, manoeuvrability, and low altitude create major challenges for defence. U.S. defence officials have noted that existing terrestrial- and space-based sensors are insufficient to detect or track such weapons. Griffin emphasised that “hypersonic targets are 10 to 20 times dimmer than what the U.S. normally tracks by satellites in geostationary orbit.” Analysts suggest that future space-based sensor layers integrated with interceptors or directed energy weapons may provide solutions, but others question whether such defences would be affordable or technologically viable.

Physicist James Acton has argued that point-defence systems such as THAAD “could very plausibly be adapted to deal with hypersonic missiles,” though he warned that these could only defend small areas. “To defend the whole of the continental United States, you would need an unaffordable number of THAAD batteries,” he explained. Other analysts have raised concerns that the current U.S. command and control architecture would be incapable of “processing data quickly enough to respond to and neutralize an incoming hypersonic threat.”

The U.S. Department of Defense is advancing several programmes through the Navy, Army, Air Force, and DARPA. The Navy’s Conventional Prompt Strike programme is leading the development of a Common Hypersonic Glide Body adapted from an Army prototype, paired with a booster to create an “All Up Round” for joint use. While early flight tests failed or were cancelled, the Department of Defense conducted successful “end-to-end” tests in June and December 2024 and April 2025. The Navy plans integration on Zumwalt-class destroyers and Virginia-class submarines, though plans for Ohio- and Burke-class vessels are not reflected in current budgets.

The Army’s Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, known as Dark Eagle, is expected to have a range exceeding 1,725 miles and provide the service with a strategic attack capability against adversary anti-access and area denial systems. Although prototype equipment has been fielded, the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation has reported that “insufficient data are available to evaluate the operational effectiveness, lethality, suitability, and survivability of the LRHW system.” Still, the Army intends to field two additional batteries by 2027.

The Air Force’s AGM-183 Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon, or ARRW, sought to use Tactical Boost Glide technology for a Mach 6.5–8 vehicle with a range of about 1,000 miles. Despite initial successes, the programme experienced a series of test failures and mixed results through 2023 and 2024. Then-Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall stated that the service was “more committed to HACM at this point in time than [it is] to ARRW.” The Air Force is now focusing on the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile, with budget requests rising to over $800 million for 2026.

DARPA has concluded several high-profile efforts, including the Tactical Boost Glide and Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept programmes, both of which contributed enabling technologies. According to former Principal Director for Hypersonics Mike White, “Project Mayhem is to look at the next step in what the opportunity space allows relative to hypersonic cruise missile systems” and is expected to explore much longer ranges than current projects.

While offensive development is accelerating, the Missile Defense Agency is also pursuing counter-hypersonic capabilities. These include the Glide Phase Intercept, a sea-based interceptor being co-developed with Japan and projected for the 2030s, and the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor system. The January 2025 executive order “The Iron Dome for America” has directed efforts to accelerate deployment of such sensors.

Despite billions invested, U.S. testing infrastructure has struggled to keep pace. The Institute for Defense Analyses reported in 2014 that no U.S. facility could replicate the full aerodynamic and thermal conditions above Mach 8. Since then, universities and government agencies have expanded wind tunnel capacity, and the Department of Defense has partnered with Australia and the United Kingdom on shared testing under the HyFliTE arrangement. However, official assessments continue to warn that testing corridors and range facilities remain insufficient to meet current demand.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy listed hypersonic weapons as one of the key technologies ensuring the United States “will be able to fight and win the wars of the future.” Congressional oversight continues to focus on ensuring the sufficiency of facilities, infrastructure, and funding. Nonetheless, as of now, the United States remains several years away from fielding an operational hypersonic capability, while Russia and China maintain deployed systems.

Source: Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for Congress (Congressional Research Service).