The United States Department of War (Pentagon) is currently implementing a programme to upgrade the avionics package of F-35 fighter aircraft to the Block 4 standard. It is also preparing to launch a programme to modernise the Pratt & Whitney F135 engines installed in the F-35.

The Block 4 upgrade includes the installation of new avionics components as part of the TR-3 (Tech Refresh 3) package as well as new avionics software. Under the TR-3 package, the fighters will receive a new onboard computer from L3Harris, a new version of the cockpit multifunction display, an upgraded Northrop Grumman AN/APG-85 radar, an upgraded version of the AN/AAQ-37 electro-optical distributed aperture system known as the Next Generation Distributed Aperture System (NGDAS), and new components of the BAE Systems AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare system. The operation of these components is to be supported by new 40-series avionics software (40R0X). The TR-3/Block 4 package replaces the previously installed TR-2/Block 3F avionics package in F-35 aircraft.

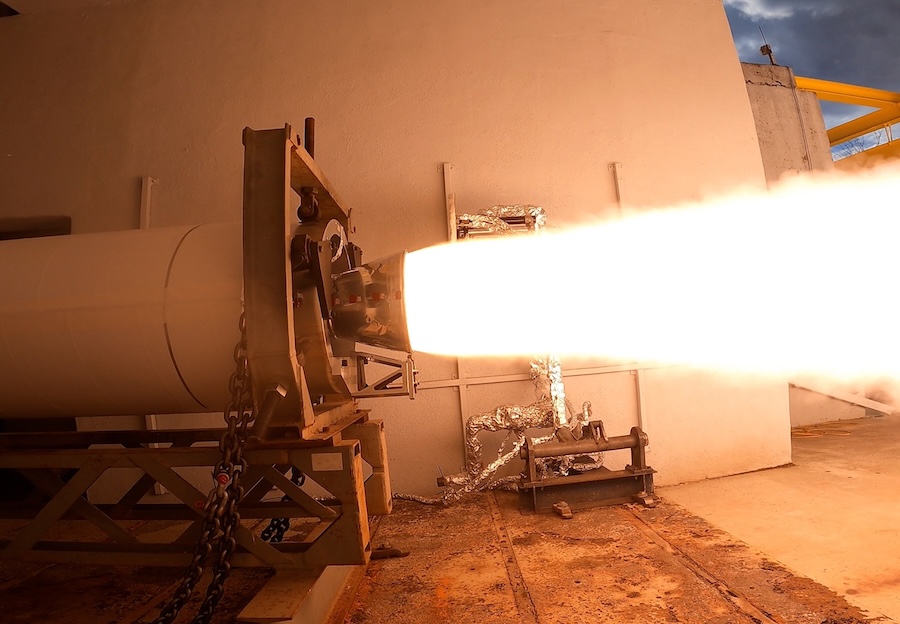

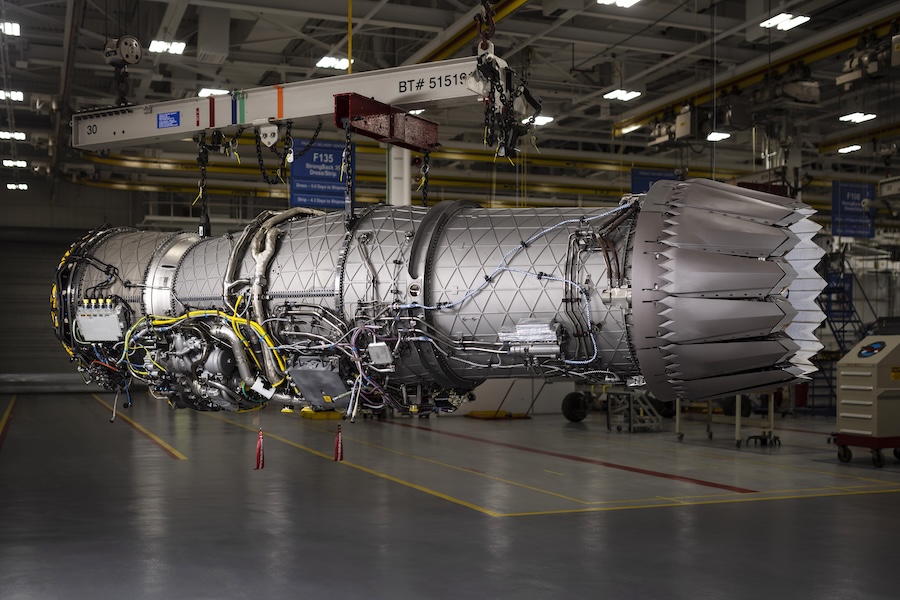

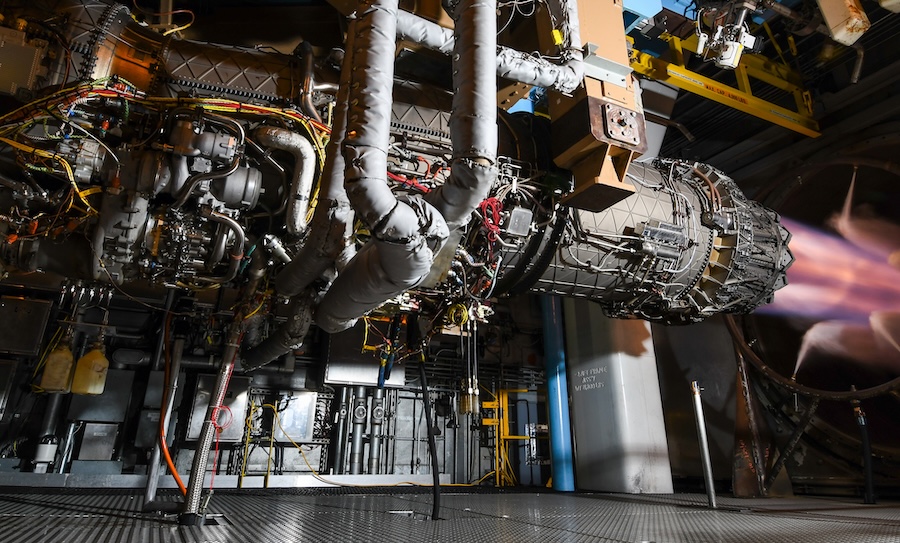

The engine upgrade programme consists of two components: ECU (Engine Core Upgrade) and PTMU (Power Thermal Management Upgrade). The ECU involves modernisation of the engine core, which consists of the power module and gearbox, while PTMU concerns the upgrade of the power and thermal management system.

According to the latest report published in September this year by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO), both the avionics and engine upgrade programmes are showing limited progress. Deliveries of F-35 aircraft equipped with TR-3 packages will not begin earlier than 2026 – three years later than originally planned. Moreover, these aircraft will still not receive the full avionics software, meaning their combat capabilities will remain limited. Meanwhile, production of components necessary for the engine upgrade process will not begin earlier than 2031–2033.

On 29 September this year, the F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) awarded Lockheed Martin a contract worth USD 24.29 billion for the delivery of 296 F-35 fighters built under production Lots 18 and 19. Deliveries of the first aircraft from these lots are scheduled to begin in 2026. The previously negotiated Lot 18 included 145 aircraft: 48 F-35A for the USAF, 16 F-35B and 5 F-35C for the USMC, 14 F-35C for the US Navy, 15 F-35A and 1 F-35B for international programme partners, and 39 F-35A and 7 F-35B for foreign customers under FMS (Foreign Military Sales). The current contract increased the number of Lot 18 aircraft to 148. Lot 19 also includes 148 aircraft: 40 F-35A for the USAF, 12 F-35B and 8 F-35C for the USMC, 9 F-35C for the US Navy, 13 F-35A and 2 F-35B for international partners, and 52 F-35A and 12 F-35B under FMS.

The average cost of a single F-35 is expected to be USD 82.4 million. This price excludes the engine, as engine procurement is contracted separately by the Pentagon with Pratt & Whitney. Including the engine, the cost of a single F-35 will increase by approximately USD 20 million. Meanwhile, finalisation of contracts for engines built under Lots 18 and 19 has been delayed by six months and is now expected in spring 2026.

Rising programme costs

In 2001, the Pentagon estimated that the total cost of development, testing and procurement of 2,470 F-35 fighters in all three variants would amount to USD 233 billion. Over subsequent years, these estimates were revised several times. In March 2012, the figure was stated as USD 396 billion, representing not only an increase of USD 163 billion but also a breach of the so-called Nunn-McCurdy Act. This legislation requires the Pentagon to notify legislators when the cost of a defence programme exceeds its budget by 15 per cent or more. Since 2012, programme costs have been revised four more times. By December 2022, estimated costs had risen to USD 442.3 billion. In December 2023, the Pentagon announced that the total programme cost would rise to USD 485.2 billion, comprising USD 87.4 billion for development, research and testing, USD 398.8 billion for procurement, and USD 4 billion for construction and infrastructure investments. Compared to 2012, this represents increases in all three categories of USD 32.2 billion, USD 58.1 billion and USD 0.8 billion respectively.

The F-35 programme office has also announced that the estimated operating cost of 2,470 F-35 fighters up to 2088 (77 years) will amount to approximately USD 1.58 trillion. Combined with development, procurement and operating costs, the total programme cost is therefore expected to exceed USD 2 trillion.

Reduction in the scope of TR-3/Block 4 modernisation

Seven years after its launch, the cost of the Block 4 avionics upgrade programme is expected to reach USD 16.5 billion. The Pentagon originally planned to spend around USD 10.6 billion on the upgrade in fiscal years 2018–2024. In 2020, this was estimated at approximately USD 14.5 billion. Development and procurement of TR-3 hardware components and development of avionics software are expected to cost around USD 1.9 billion.

Since its inception, the TR-3/Block 4 upgrade programme has been part of the overall F-35 production programme. Under the defence budget act for fiscal year 2024, legislators required the Pentagon to separate the TR-3/Block 4 upgrade as a main subprogramme. As a result, it will receive its own budget and schedule, independent of the main F-35 programme. This process is due to be completed by the end of the current year, giving legislators greater insight and control over expenditure and enabling easier monitoring of progress.

Delays and cost increases in the TR-3/Block 4 upgrade are linked on the one hand to problems finalising the avionics software and on the other to delayed deliveries of hardware components, many of which still require further refinement.

In January 2023, test flights began of an F-35A aircraft fitted with some TR-3 package components. However, due to the immaturity of the avionics software in the so-called reduced 40R01 version, only part of the planned tests were completed by the end of 2023. These revealed significant software instability, requiring further corrections. As a result, in July 2023 the Pentagon suspended acceptance of F-35 fighters, forcing Lockheed Martin to store completed aircraft. Although exact figures were not disclosed, more than 100 F-35 aircraft were placed in storage. Acceptance resumed only in July 2024, with the Pentagon ultimately agreeing to accept fighters equipped with the downgraded TR-3/Block 4 package and 40R01 software. These aircraft do not possess full combat capabilities and are suitable only for training flights. By May 2025, the Pentagon had accepted 174 F-35 aircraft with the downgraded TR-3/Block 4 package, including all aircraft previously stored by Lockheed Martin. In July 2025, the process of installing expanded avionics software in these aircraft was due to begin, enabling limited combat capability. At present, the Pentagon does not plan to install TR-3/Block 4 packages on F-35 aircraft already equipped with the TR-2/Block 3F avionics package. Consequently, over a thousand currently operated F-35s will not be upgraded.

Lockheed Martin admitted that all issues with the onboard computer installed under the TR-3 package were resolved only by mid-2025. The unit had to be refined to meet programme specifications, as it did not fulfil requirements, and issues with insufficient component quality also had to be addressed. The NGDAS system has still not been finalised and remains in the testing and validation phase, which is due to be completed in 2026.

By mid-2024, it was expected that the fully functional target avionics software, designated 40R02, would be implemented in spring 2025. However, in late January 2025, Lockheed Martin admitted that achieving full operational capability of the TR-3/Block 4 package with 40R02 software would not be possible earlier than 2026. According to the GAO report, the F-35 programme office now plans to introduce an incomplete version of the TR-3/Block 4 avionics package. The specific capabilities to be reduced have not yet been disclosed. Implementation of this “scaled-down” package is planned for completion by 2031. Any potential expansion of capabilities will only be possible in the mid-2030s. While the precise scope remains unknown, the costs of the TR-3/Block 4 upgrade are certain to rise yet again.

Delayed aircraft and engine deliveries

Over the past few years, both Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney have been delivering aircraft and engines with increasing delays.

By May 2025, the Pentagon had accepted 80 aircraft, including 74 that were due for delivery in 2023 and 2024. Lockheed Martin still has to deliver 20 aircraft scheduled for 2024. The negative trend began in 2018, when of 91 F-35s built, only 53 were delivered on time. In 2019, 118 out of 134 were delivered on time. In 2020, only 70 of 120 were delivered on time; in 2021, 120 of 142; in 2022, 70 of 141; and in 2023, only 9 of 98. In 2024, due to the Pentagon’s suspension of acceptance, none of the 110 completed aircraft were delivered. Whereas in 2022 deliveries were on average 22 days late, in 2023 the figure rose to 61 days, and in 2024 reached 238 days.

One of the main factors behind these delays is the late delivery of certain components and parts by subcontractors. However, the problem also affects parts produced by Lockheed Martin itself. A notable example is the leading-edge flaps of the wings, whose delayed delivery since 2023 has been a major factor impeding production. The shortage of parts results in an accumulation of incomplete aircraft awaiting delivery. According to the programme office, in February 2025, 52 incomplete aircraft were unable to leave the production line for this reason. The Defence Contract Management Agency (DCMA) reported that at the beginning of 2025, Lockheed Martin was awaiting more than 4,000 different parts and components required to complete F-35 production, including around 1,600 parts used in the TR-3/Block 4 avionics upgrade programme.

Logistical and material problems may become the main obstacle to scaling up F-35 production. According to Lockheed Martin, production is soon expected to reach a maximum of approximately 156 aircraft per year, a level to be maintained over the next five years. However, the company is currently unable to build even 150 F-35s annually, let alone deliver them on schedule.

In 2024, Pratt & Whitney delivered all 123 engines produced after the deadline. The same situation occurred the previous year, involving all 137 engines built. In 2022, only four of 127 engines were delivered on time, and in 2021 just six out of 152. The average delay was 22 days in 2022, rising to 61 days in 2023 and reaching 238 days in 2024.

As with the aircraft, these delays stem from problems with timely delivery of components by subcontractors, as well as engines failing initial quality checks and manufacturer testing. Pratt & Whitney also suspends deliveries if any quality issues are detected in installed components. Lockheed Martin maintains a certain buffer stock of engines, meaning that for now, delayed engine deliveries do not affect the fighter production process.

Ineffective financial incentives

The GAO report criticises the policy of the F-35 programme office, which financially rewards Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney despite their failure to deliver products on time.

Under Pentagon contracts, manufacturers earn a fixed percentage of the price of each delivered aircraft or engine. The contracts also include clauses allowing the programme office to award bonuses if quality performance improves, deliveries are on time, or if producers demonstrate initiatives leading to reduced prices. In the event of performance deterioration, penalties may be imposed, reducing base profits by a set percentage. Such penalties were applied when the Pentagon suspended aircraft acceptance due to the unfinished avionics package, reducing payments to Lockheed Martin by USD 5 million per aircraft, later lowered to USD 3.8 million as the programme progressed.

However, in terms of delivery timeliness, manufacturers are rewarded even when deadlines are significantly exceeded. In 2021–2022, under Lot 13, Lockheed Martin delivered 93 F-35s, 29 of them late, with an average delay of 20 days. Despite this, the manufacturer received a timeliness bonus reduced by only 7 per cent. Under Lot 14 (2022–2023), 77 of 96 aircraft were delivered late, with an average delay of 65 days, yet the bonus was reduced by just 35 per cent.

The situation is similar for Pratt & Whitney. Bonuses are paid if engines pass quality inspections, are built according to schedule and delivered on time, with delivery timeliness being only one of several factors. Under Lot 14 (2021–2022), 80 of 82 engines were delivered late, resulting in a 44 per cent reduction in bonuses. Under Lot 15 (2022–2023), all 89 engines were delivered late, yet bonuses were reduced by only 11 per cent. Under Lot 16 (2023–2024), all 66 engines were delivered late and bonuses were reduced by 63 per cent.

GAO stresses that there is no mechanism incentivising manufacturers to improve performance and that the current reward system has the opposite effect. For example, contracts for Lots 15–17 allow bonuses if delivery delays do not exceed 75 days, with reductions starting only after an additional 15 days. Thus, only if Lockheed Martin begins delivering fighters with a 90-day delay can it expect bonuses to be reduced, though not entirely withheld.

Delayed engine upgrade programmes

The Engine Core Upgrade (ECU) programme began in March 2023. The F-35 programme office commenced analysis of options to increase engine power while improving its ability to generate electricity and cool increasingly advanced avionics systems. The upgrade is intended to extend engine service life and maintain combat capability of the F-35 beyond 2029. It is also key to implementation of the TR-3/Block 4 avionics package and its future versions, as these will exacerbate the problem of insufficient power and cooling capacity of the F135 engine. The ECU upgrade will not alter the external dimensions or overall configuration of the engine, allowing it to be applied across all three F-35 variants.

As early as May 2023, GAO recommended that the ECU programme be separated as a major defence subprogramme to improve management and pace of implementation. The first Preliminary Design Review (PDR) was conducted in February 2024, with the second completed in mid-July 2024. Despite positive outcomes, no development and test schedule was established at that time, nor was the necessary material base for testing created. In September 2024, JPO awarded Pratt & Whitney a USD 1.3 billion contract for the risk reduction and technology maturation phase of the ECU programme, to be completed by the end of 2026. Only then can the first contract under the subsequent development phase be awarded. GAO notes that two key turbine technologies intended for use have not yet been fully developed. If the first development-phase contract is awarded in 2027 as scheduled, production of upgraded F135 engines will likely begin no earlier than 2031.

The PTMU programme is even less advanced than ECU. It includes several initiatives aimed at modernising subsystems such as the Power and Thermal Management System (PTMS), responsible for distributing cooling air for avionics components, the fuel temperature management system, and the power generation system. At the beginning of 2024, the programme office considered various options, including upgrading existing subsystems or developing entirely new ones. Ultimately, in December 2024, Lockheed Martin was awarded a USD 107 million contract to analyse available options and identify potential technologies, with the analysis to be completed by December 2026. Only after this will the JPO decide on specific upgrades or modifications. The development phase of the PTMU programme may begin no earlier than 2027, meaning production of new components would potentially commence only in 2033. The total costs of both programmes remain unknown, though development and testing phases are estimated at approximately USD 4.5 billion, with additional costs for production and installation of required components.

This article was originally published in the monthly magazine Lotnictwo Aviation International, issue 10/2025. The title has been changed by the editorial team of Defence Industry Europe.