Rome is pursuing the programme together with the United Kingdom and Japan, with the aim of joining a limited group of countries able to design and govern next-generation combat aircraft systems. The initiative reflects a possible change of course from earlier projects in which Italy’s access to technology and operational control remained constrained.

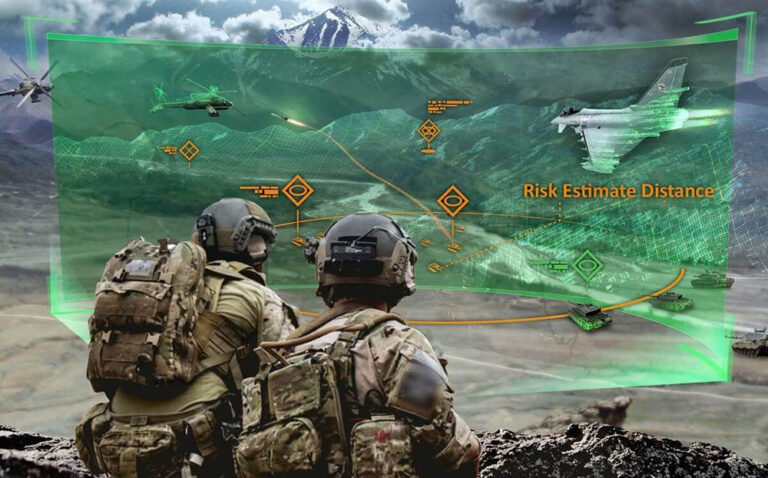

The Gcap is the result of merging the British Tempest programme with Japan’s FX project and targets the development of a sixth-generation air combat system by 2035. The future platform is intended to progressively replace aircraft such as the Eurofighter Typhoon and the Mitsubishi F-2, while operating as an integrated system in complex and allied warfare environments.

Italy’s contribution to the development phase is estimated at around €9 billion until 2035, according to the Defence Multi-Year Planning Document. This figure excludes future production and life-cycle costs, with funding for 2025 alone exceeding €600 million and possible revisions anticipated as the programme evolves.

The Gcap is expected to operate alongside Italy’s existing fleets before gradually replacing them, with 118 Eurofighters currently in service and a target of 115 F-35s. By around 2040, Italy plans to field more than 180 combat aircraft across these platforms during the transition phase.

The programme also aims to reduce Italy’s gap in uncrewed combat air systems by developing advanced auxiliary platforms linked to the main fighter. As Alessandro Marrone, head of the Defence, Security and Space programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali, explains, “We need to equip ourselves looking ahead to the next 10, 20, 30 years to maintain deterrence against Russia and, more generally, to contain Russia and Chinese assertiveness in various regional quadrants.”

Unlike the F-35 programme, which generated strong political divisions in Italy, the Gcap has so far benefited from broader cross-party support. The F-35 cooperation model was heavily centred on the United States, which retained control over key technological and operational choices after covering most research and development costs.

An Istituto Affari Internazionali report noted that “The limited transfer of technology and the presence of ‘black boxes’ in the F-35 programme frustrated Italian actors.” In contrast, the Gcap is based on equal access to technology and an equal 33.3% industrial share for Italy, the United Kingdom and Japan, offering Rome greater operational and technological autonomy.

Internationally, other powers are pursuing similar ambitions through different frameworks. The United States is developing two separate next-generation aircraft programmes, while France, Germany and Spain are working on the Future Combat Air System, a trilateral project combining a piloted aircraft, armed drones and an integrated combat cloud.

Despite significant political and financial backing, the Future Combat Air System has faced delays and industrial tensions, particularly in Franco-German cooperation. Its entry into service is currently expected around 2040, approximately five years later than the Gcap’s target timeline.

For Italy, analysts stress that the Gcap remains a high-risk undertaking due to its scale and complexity. The integration of a sixth-generation fighter, drones, advanced communications and open digital architectures will require sustained coordination, secure handling of classified information and consistent long-term funding to deliver the promised industrial and technological returns.

Source: Euronews.