Counter-drone spending in particular is exploding, driven by Ukraine, Gaza and daily drone incursions across NATO airspace, with the EU pledging billions to build a new ‘drone wall’ along its eastern flank. Yet for all the activity, capability isn’t catching up. Most counter-unmanned aerial systems (C-UAS) purchased today are outdated before they are even deployed.

This is becoming more problematic. In late October, unauthorised drones flew over a Belgian army base, one of dozens of similar incidents across Europe this year, including in Germany, Norway and Poland. The EU may spend a projected €381 billion on defence in 2025, but our ability to detect and stop a $1,000 drone remains alarmingly inconsistent.

Market reality

The problem is what the money is buying. Today’s C-UAS market is polarised. On one side are easy-to-manufacture, cheap and cheerful gadgets: handheld jammers and disposable interceptors that are lightweight and easy to deploy at scale, but can’t reliably protect a platoon, let alone a brigade. On the other side, there are billion-euro programmes that deliver impressive performance but are too expensive to deploy because they rely on costly planes and missiles. Across Europe, the market is being flooded with these contrasts. The technology may look impressive on slides, but it’s answering the wrong question.

The result is a widening gap between cheap but ineffective and effective but unaffordable. Militaries are desperate for systems that actually work, systems which are mid-cost, deployable, scalable solutions that can protect troops and infrastructure in real-world conditions. That middle ground is where the real fight will be won, but right now, almost nobody is filling it.

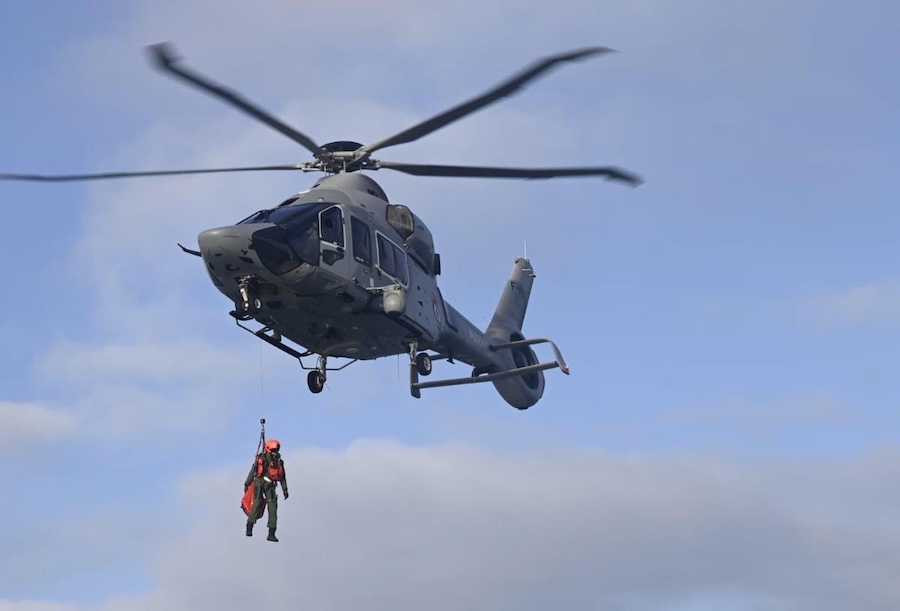

Meanwhile, the threat evolves faster than procurement cycles. In Ukraine, $500 FPV drones are destroying multi-million-dollar vehicles. In Poland in September, NATO was forced to scramble $100 million F-35 jets that cost $35,000 an hour to fly and fire $1 million missiles to intercept drones that likely cost no more than $20,000 a piece. These aren’t anomalies; they’re evidence that our defences remain economically and operationally mismatched to the threat. On the other side of the equation, numerous companies are rushing to bring “low-cost” ground-based interceptors to market, but the geographic constraints of being launched from the ground, as well as the hardware constraints of being single-use, mean that the detection range and targeting reliability of these interceptors are limited. In a large-scale fight, ‘cost-per-unit’ is less important than ‘cost-per-kill’; deploying a ‘low cost’ interceptor that has limited effective range and a 20% success rate will result in a capability that has both a lower effective range and a higher cost-per-kill.

The commercial logic is just as broken. When interceptors become low-margin commodities, producers compete on price rather than performance. When high-end systems dominate, cost prevents scale. Either way, innovation stalls, and militaries end up with fewer options that cost more.

Europe needs alignment

Some policymakers are starting to see the issue. The EU’s new €150 billion SAFE facility, aimed at joint defence acquisition and innovation, explicitly includes counter-drone technology. It’s a step in the right direction. But funding alone won’t close the gap unless procurement frameworks evolve.

Europe currently has a procurement logic problem, with a lack of alignment between what’s being built and what’s actually needed on the ground.

We need systems that are attritable – systems that sit somewhere between the traditional exquisite systems built by established firms, and disposable systems that a lot of newer market entrants are focusing on. Attritable systems should be those that are effective enough to reliably detect and defeat threats at range, but affordable enough that losing a few isn’t going to bankrupt the country. These systems also need to be quickly deployable, easy to field, fast to update, and built to work alongside what militaries already have. This was part of the drive behind founding my company, Alpine Eagle. To protect Europe, we need to focus on the centre, delivering the missing middle that bridges cost and capability.

If Europe continues to spend billions on technology that can’t deploy fast enough, adapt fast enough, or scale far enough, it will keep losing the first fight, the fight for relevance. The drones aren’t waiting for our procurement cycles to catch up. Neither should we.