WORLD’S MOST PEACEFUL COUNTRY

Iceland often referred to as the Land of Fire and Ice, is a small island country in the North Atlantic Ocean wedged between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. There are around 376,000 people living there, and it is renowned for its breathtaking natural features, which include glaciers, active volcanoes, geysers, and hot springs. The nation is regarded as one of the most peaceful and rich in the world and has a distinctive political structure.

Iceland has consistently been ranked as the world’s most peaceful country by various organizations and academic studies. The Global Peace Index, which is produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace, has ranked Iceland as the most peaceful country for the past decade, as well as for 2022. This index measures peace based on factors such as levels of violence and crime, militarization, and the number of internal and external conflicts. Another study, published in the Journal of Peace Research, found that Iceland has the lowest level of political violence in the world. The study, which analyzed data from over 150 countries from 2000 to 2010, found that Iceland had no reported incidents of political violence during this time period. One instance is from the period following the financial crisis in 2008, when many people feared that internal strife might result from civil disobedience. Communities instead got together to figure out how to improve their immediate environment. Additionally, a study by the European Journal of Criminology found that Iceland has the lowest crime rate in the world. The study analyzed data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and found that Iceland had the lowest per capita rate of crime among all countries. Overall, Iceland’s low levels of violence and crime, as well as its lack of political and military conflicts, have consistently placed it at the top of rankings for the world’s most peaceful country.

NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY OF ICELAND

One of the most notable characteristics of Iceland is that it has no military. The country has never had a standing army and has relied on other countries for protection since it gained independence from Denmark in 1944. Iceland is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and has participated in various international peacekeeping missions through the organization. Iceland’s NATO membership, alongside the 1951 Bilateral Defense Agreement with the United States of America continues to be the two primary cornerstones of Iceland’s security strategy. Furthermore, the country has a defense agreement with Norway, which includes cooperation on maritime surveillance, search and rescue, and other defense-related activities, while simultaneously, the US has had a military presence in Iceland since World War II, and maintains a small number of troops and air defense assets in the country. Iceland’s lack of a military is a result of factors such as its small population, while its remote location makes it less likely to be targeted by foreign invaders, given the fact that the supply chain of any potential invader would be extremely difficult over hundreds of kilometers of open ocean. On top of that, the country has always had a strong tradition of neutrality and has avoided getting involved in military conflicts. Henceforth, this is why Iceland’s defense is the responsibility of NATO, which has a presence in the country through the Iceland Defense Force, which is a small unit of soldiers from other NATO countries who are stationed in Iceland to provide security and protect the country’s airspace.

Another important aspect of Iceland’s national security policy is its focus on peaceful resolution of conflicts. The country has a long history of participating in peacekeeping and conflict resolution efforts through organizations such as the United Nations and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Iceland also places a strong emphasis on humanitarian and peacekeeping operations and has contributed troops and resources to various missions around the world. In addition, the country has a strong coast guard and emergency management system in place to respond to natural disasters and other crises. At the same time the country’s participation in various international agreements and treaties, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Antarctic Treaty. These agreements help to promote stability and cooperation in the international community. Iceland also places a strong emphasis on international cooperation and collaboration in its national security policy. The country is a member of the Nordic Defense Cooperation Organization (NORDEFCO), and also participates in various international security initiatives and exercises through its membership in NATO’s Partnership for Peace program.

THE COD WARS & ICELAND’S EXCLUSIVE FISHING LIMITS

The Iceland Coast Guard (ICG) is the national maritime law enforcement agency of Iceland. It is responsible for maritime safety, search and rescue operations, and enforcing maritime laws and regulations within Iceland’s territorial waters and exclusive economic zone.

Icelandic Coast Guard ships would break the trawl cables of British and West German trawlers, leading to clashes with Royal Navy vessels, during the fishing rights conflict known as the Cod Wars, which occurred between 1972 and 1976. That was when the Coast Guard played its largest role. The disputes began in 1958, when Iceland extended its fishing limit from 4 nautical miles to 12 nautical miles, a move that was met with resistance from the UK. The conflict escalated in 1972 when Iceland extended its limit to 50 nautical miles and again in 1975 when it extended the limit to 200 nautical miles. The Cod Wars were mostly peaceful, but there were some incidents of clashes between naval vessels and fishing boats, and some arrests were made. Ultimately, the disputes were resolved through negotiations and the UK recognized Iceland’s extended fishing limits in 1976.

The exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Iceland extends 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) from the coastal baseline of the country, as established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This means that Iceland has sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve, and manage the natural resources within this zone, both living and non-living, such as fish, minerals, and energy. The EEZ of Iceland is significant as it encompasses an area of around 890,000 square kilometres, making it one of the largest in Europe.

THE GEOPOLITICAL IMPORTANCE OF ICELAND

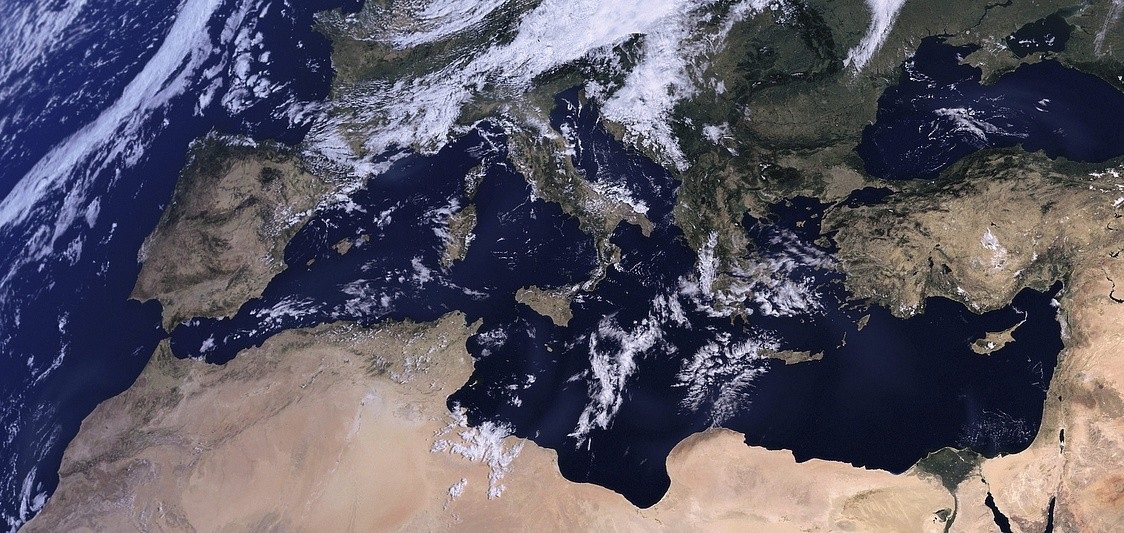

Iceland has historically been of geopolitical importance due to its strategic location between Europe and North America, as well as its abundant natural resources and thriving fishing industry as it has played a significant role in its economy and has made Iceland an important player in international fisheries management. In recent years, Iceland has extended its diplomatic capacity, particularly in the Arctic region, as the country has been an active member of the Arctic Council and has played a role in promoting sustainable development and environmental protection in the region. Moreover, its location makes it a valuable partner for other countries in monitoring and responding to security threats in the North Atlantic.

THE ARCTIC SHIPPING ROUTES

The Arctic shipping routes refer to the waterways that pass through the Arctic Ocean, connecting Europe and Asia. These routes have gained increased attention in recent years due to the melting of Arctic ice, which has made them more accessible for commercial shipping while having the potential to reduce the distance between Europe and Asia by up to 40% compared to traditional routes through the Suez Canal. Nonetheless, the Arctic shipping routes have the potential to provide significant economic benefits for shipping companies, but also raise concerns about their environmental impacts.

Iceland’s location, along with its relatively mild climate and well-developed infrastructure, make it an attractive destination for shipping companies looking to take advantage of the growing demand for arctic shipping routes. One of the main arctic shipping routes that pass through Iceland is the Northeast Passage, which runs along the northern coast of Russia and through the Arctic Ocean. This route has become increasingly popular in recent years as climate change has caused the Arctic sea ice to melt, making it more navigable for larger vessels. Another important arctic shipping route, the Northwest, that passes through Iceland is running through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and the Beaufort Sea. This route is considered to be more challenging than the Northeast Passage due to the presence of sea ice and unpredictable weather conditions. In addition to those, there is the Transpolar Sea Route as well, which runs across the Arctic Ocean, and the Northern Sea Route, along the northern coast of Russia. These routes have the potential to significantly reduce shipping times and costs for shipping companies, making them an increasingly attractive option for global trade.

THE GUIK GAP

The Arctic GIUK (Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom) Gap is a strategically important region in the Arctic that plays a crucial role in global security, economic stability and rich natural resources, including oil, gas, and minerals, as it provides a shorter and more cost-effective route than traditional routes through the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal. This region is known for its strategic importance as it provides access to the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic. The region is home to several military bases and is an important area for military training and exercises. Concluding, The Gap is also considered to be a potential flashpoint for conflicts between countries due to competing claims over natural resources.

EXTERNAL RELATIONS OF ICELAND

Iceland’s geographic isolation and small population have traditionally limited its ability to project power and influence beyond its borders. However, its strategic location in the North Atlantic has also made it a key stakeholder in regional security and cooperation, particularly in the areas of fisheries, energy, and transportation. Iceland’s memberships in the Nordic Council and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) have also had a strong influence on its foreign policy. The country has traditionally emphasized the importance of multilateralism and peaceful resolution of conflicts and has sought to maintain close relations with both the United States and Europe.

RUSSIA – ICELAND BILATERAL RELATIONS

In recent years, Iceland and Russia have developed a more cooperative relationship, with both countries engaging in a number of economic and diplomatic initiatives. In 2013, the two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the Arctic, which aimed to increase cooperation in areas such as research, environmental protection, and economic development. In addition, Iceland and Russia have also cooperated in other areas such as fishing, tourism, and energy. For instance, they have cooperated on fishing quotas and have also established a Joint Fisheries Commission to manage the shared fish stocks in the Barents Sea. Furthermore, Russia has become an increasingly important market for Icelandic tourism, with many Russian tourists visiting Iceland each year. Additionally, Russia provides Iceland with natural gas and oil for its energy needs.

Despite these positive developments, there have also been some challenges in the relationship between the two. In 2014 annexation of Crimea by Russia caused tensions between the two, as Iceland, along with other Western countries, condemned the annexation and imposed economic sanctions on the Kremlin, in addition to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

CHINA – ICELAND BILATERAL RELATIONS

In 2008, Iceland became the first Western country to sign a free trade agreement with China, which helped to boost economic ties between the two. This agreement has been beneficial for both, as Iceland has been able to export more fish and other seafood to China, and China has been able to import more Icelandic geothermal energy technology. In addition, Iceland and China have also cooperated on issues related to climate change and Arctic affairs. In 2013, the two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Arctic Cooperation, which has led to joint research projects and other forms of collaboration, such as the China-Iceland Arctic Science Observatory. The two countries came closer after Iceland withdrew its EU application in 2015.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a Chinese-led infrastructure development project that aims to connect Asia, Europe, and Africa through a network of roads, railways, ports, and other infrastructure projects. Henceforth, Iceland’s location makes it a strategic point for transportation and trade between Europe and North America. The BRI’s focus on infrastructure development could provide Iceland with opportunities to develop its transportation and trade networks, such as the Arctic Silk Road which could connect Asia to Europe through the Arctic Ocean, providing Iceland with a new trade route to Asia. According to a study by the China Institute of International Studies, Iceland’s participation in the BRI could lead to increased trade and investment between China and Iceland, which could lead to economic growth for Iceland, but also to a potential risk of increased debt and dependence on China.

As a response, in 2019 the Pentagon spent 80 million dollars to upgrade runways to Keflavik airport in Iceland, to help NATO surveillance missions, and to boost the US presence in key passageways in the Arctic to counter Chinese and Russian activities.

AN INTEGRAL PART OF NATO

Overall, Iceland as a member of NATO plays an important role in the organization’s security and defense efforts to protect its northern flank and to monitor and control maritime activity in the region, for its geostrategic locations, given the installation of the Iceland Air Surveillance System (IASS) which is responsible providing early warning of potential threats and for coordinating the response of NATO’s military assets to any potential crisis. The country’s strategic location and its extensive experience in Arctic operations make it an important partner in NATO’s efforts to address security challenges in the region. Furthermore, Iceland is actively involved in the NATO Defense Planning Process and the NATO Strategic Concept, which are important frameworks for the organization’s defense and security efforts. Overall, Iceland’s location, operational capabilities, and policy contributions make it an important member of NATO and a key partner in the organization’s efforts to maintain security and stability in the North Atlantic and Arctic regions.

Concluding, as Bjarni Benediktsson, the Foreign Minister of Iceland Speaking at the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty Washington, D.C. in 1949, said: “My people are unarmed and have been unarmed since the days of our Viking forefathers. We neither have nor can have an army…but our country is, under certain circumstances, of vital importance for the safety of the North Atlantic area.”

RESOURCES

- Image source: http://veimages.gsfc.nasa.gov/6605/Iceland.A2004028.1355.250m.jpg

- Institute for Economics & Peace. (2022). Global Peace Index 2022. Available at: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GPI-2022-web.pdf

- Journal of Peace Research. (n.d.) Sage Publication Ltd

- Omarsdottir, S. (2017). The Most Peaceful Country in the World: The Meaning of Peace in Iceland. The European Consortium for Political Research. Available at: https://ecpr.eu/Events/Event/PaperDetails/33310

- Ólafsdóttir, H. & Bragadóttir, R. (2016). Crime and Criminal Policy in Iceland: Criminology on the Margins of Europe. European Journal of Criminology. European Society of Criminology

- Webel, C & Galtung, J. (2007). Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies. Routledge

- Global Security. (2012). Iceland Defense Force. Available at: https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/dod/idf.htm

- (2007). Norway, Iceland sign defence cooperation deal. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/norway-iceland-defence-idUKL2672017520070426

- Iceland and NATO. (n.d.). North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Available at: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_162083.htm

- Hreinsson, H. (2010). Icelandic Foreign Policy: From Neutrality to Partnership. Journal of Baltic Security

- Arnesen, S. (2017). Iceland and NATO: The Evolution of a Partnership. Journal of Conflict and Security Law

- Gunnarsdóttir, B. (2007). Iceland’s Foreign and Security Policy. International Affairs

- Icelandic Ministry for Foreign Affairs. (n.d.) Iceland’s Foreign Policy. Stjórnarráð Íslands

- Icelandic Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (n.d.) Iceland’s National Security Policy. Stjórnarráð Íslands

- World Maritime University. (2018). WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs. Springer

- Landhelgisgæsla Íslands. (n.d.). The Icelandic Coast Guard. Available at: https://www.lhg.is/media/LHG80/Landhelgisgasla_Islands_enska2_.pdf

- Jóhannesson, G. (2004). Troubled Waters. Cod War, Fishing Disputes, and Britain’s Fight for the Freedom of the High Seas, 1948-1964. Academia. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2555064/Troubled_Waters_Cod_War_Fishing_Disputes_and_Britains_Fight_for_the_Freedom_of_the_High_Seas_1948_1964

- BBC News. (2016). The fish that nearly caused a war. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/av/magazine-35431070

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. (1982). Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

- Hayward, J. (n.d.). The United States and Iceland: A Study in the Evolution of a Small Power-Great Power Relationship

- Gunnarson, P. & Thorhallsson, B. (2017). Iceland’s Relations with its Regional Powers: Alignment with the EU-US sanctions on Russia. Available at: https://nupi.brage.unit.no/nupi-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2441710/NUPI_Working_Paper_874_Thorhallsson_Gunnarsson.pdf

- Arctic Institute. (2018). The Northeast Passage: An Emerging Arctic Shipping Route.” Arctic Institute.

- Romanovsky, V. & Romanovsky, N. (2016). The Arctic Shipping Routes: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering

- Einarsson, G. & Jonsson, A. (2015). Maritime Transportation in the Arctic: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice

- Kupriyanov, A. & Hulsman, J. (2015). Arctic Shipping: Risks and Opportunities. Journal of Geopolitical Affairs

- Koivurova, T. & Tuohimaa, T. (2014). Arctic Shipping and the Northern Sea Route. Journal of Transport Geography

- Lehti, M. & Ollikainen, M. (2013). The Northern Sea Route: Opportunities and Challenges for Shipping. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy

- Penttilä, Ri. (2013). Arctic Shipping: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy

- Neimeyer, J. (2015). The Arctic GIUK Gap: An Overview. Journal of Strategic Studies

- Fingar, H. (2017). The Arctic GIUK Gap: A Geopolitical Analysis. Journal of Strategic Studies

- Webster, D., Bradshaw, M., & Duyvesteyn, J. (2010). The Arctic: A new frontier for oil and gas. Energy Policy

- Kaarstad, J. & Skogdalen, O. (2014). The Arctic GIUK Gap: A Strategic Area of Interest. Journal of Strategic Studies

- Eiríksson, G. (2015). Iceland’s foreign policy: Small state identity and role conception in a changing world. Routledge.

- Sigurgeirsson, G. (2017). Iceland’s foreign policy: Between neutrality and NATO. Routledge.

- Jóhannesson, G., & Eiríksson, G. (2013). Iceland’s foreign policy: From neutrality to membership. Routledge.

- Sigurgeirsson, G. & Eiríksson, G. (2015). Iceland’s Arctic foreign policy: Opportunities and challenges. Springer.

- Gudmundsdottir, G. & Gudnason, V. (2018). Russian tourism to Iceland: A qualitative analysis of Russian tourists’ experiences. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change

- Hoffmann, J. (2013). Russia and Iceland sign Arctic cooperation agreement. Arctic Journal.

- Jóhannsdóttir, B., & Ólafsson, G. (2014). Iceland and Russia: A delicate balancing act. Journal of Baltic Security

- Jóhannsdóttir, B. (2017). Iceland and Russia: Cooperation in the fisheries sector. Journal of Baltic Studies

- Sigurgeirsdottir, G., & Ólafsson, G. (2016). Iceland and Russia: Cooperation in the energy sector. Journal of Energy Security

- Chen, L. (2017). Iceland’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative: Opportunities and challenges. China Institute of International Studies.

- Lanteigne, M. (2010). Northern Exposure: Cross-Regionalism and the China—Iceland Preferential Trade Negotiations. Cambridge University Press.

- Guschin, A. (2015). China, Iceland and the Arctic. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2015/05/china-iceland-and-the-arctic/

- Doshi, R., Huang, A. & Zhang, G. (2021). Northern expedition: China’s Arctic activities and ambitions. Brookings. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/northern-expedition-chinas-arctic-activities-and-ambitions/

- Government of Iceland. (n.d.). Iceland Air Surveillance System. Available at: https://www.government.is/diplomatic-missions/permanent-delegation-of-iceland-to-nato/iceland-and-nato/#:~:text=Iceland%20operates%20an%20air%20defence,Air%20Command%20and%20Control%20System

- (2022). Chair of the NATO Military Committee highlights strategic importance of the Arctic. Available at: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_208099.htm

- Jóhannesson, G. (1994). Iceland’s Defense and Security Policy: A Study in Non-Alignment. Journal of Peace Research

- Þórðarson, Ó. (1999). Iceland and NATO: The First Fifty Years. Journal of Strategic Studies

- Jóhannesson, G. (2005). NATO’s Partnership with Iceland: A Study in Small State Cooperation. Journal of Peace Research