STATUS QUO

The Taliban, predominantly ethnically Pashtun, emerged from the political arena of Afghanistan in 1996, when they established themselves in Kabul and changed the name of the country from the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. In the 1990s, only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates recognised the Taliban government, which already at that time was providing a flourishing environment for the transnational jihadist group to expand and exert pressure on the region, like al-Qaeda. The Islamic fundamentalist group of the Taliban ruled Afghanistan until November 2001, when a coalition led by the US overthrew the movement.

Following al-Qaeda’s attacks of the World Trade Centre in New York and the Pentagon in Washington DC on September 11, 2001, the Americans responded with Operation Enduring Freedom on October 7, marking the beginning of the Global War on Terror. The Operation led to the fall of Kabul on November 13, 2001, whereby the Taliban were forced to leave the capital and hide in northern Afghanistan. On December 5, 2001, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 1383 paved the way for the Bonn Agreement which established an interim authority in Afghanistan whilst giving the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) the power to assist Afghanistan in its political transition. It is important to note that the Taliban were excluded from the Bonn Agreement, as it was unthinkable that the Americans and the Taliban would sit around a table and discuss the political and social reconstruction of Afghanistan together at that time. However, cutting ties with the Pashtun and preventing their participation in nation-building would already foster a general sense of malaise amongst the Taliban. As a result of the Bonn Agreement, a period of reconstruction of Afghan society began with the collaboration of several Western actors, primarily led by the US. The common objective was to build a democratic system without the interference of the Taliban or other terrorist groups. Nevertheless, as it has become clear, nation-building failed in Afghanistan and whilst the Taliban were informally creating a parallel state structure funded by opium and illegal mining, Western influence in Afghanistan was inefficiently spent in security and humanitarian missions.

After two decades in which the West tried to export democracy to Afghanistan, on February 29, 2020, the Trump Administration and Taliban co-founder Mullah A.G. Baradar signed the Doha Agreement thanks to the relevant Pakistani collaboration. The latter had a crucial role in the diplomatic dialogues that led to the Doha Agreement, as Pakistan never revoked its support to the Taliban. On the other hand, the representatives of the Afghan government in Kabul did not participate in the discussion. Specifically, the Agreement aimed at a full withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan within fourteen months (Doha Agreement, February 29, 2020). In exchange for this, the Taliban pledged to prevent any terrorist activity on their territory. In doing so, they obtained what they wanted without making a single concession to the Americans and the West. As no official ceasefire was put in place and no intra-Afghan peace dialogue started, violence continued to escalate in the country between 2020 and 2021, in particular against the Afghan government. Following the almost-complete withdrawal of American troops by the end of July 2021, the Taliban’s violence culminated in the assault of Kabul on August 15, 2021. The former elected government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, whose president was M.A. Ghani, collapsed, thereby leading to the restoration of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) on September 7, 2021. As a result, the Afghan constitution of 2004 was suspended and several Ministries and political departments abolished, like the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the State Ministry for Peace Affairs, and the State Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs.

Following the halting of humanitarian funds after the fall of Kabul, the plight of Afghan society led by the Taliban is worsening. Women’s rights have been curtailed, and food insecurity is on the rise – with 18.9 million people deemed acutely food insecure according to the May 2022 Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) Analysis. The economic situation is also on the verge of collapse, the agriculture sector is dire and hit by heavy droughts, and the cultivation of opium poppies has increased by 32% since last year, causing an intensification of drug trafficking towards Russia in particular (UNODC, 2022). Additionally, the killing of al-Qaeda’s former leader in Kabul A. al-Zawahiri on July 31, 2022, is evidence that the Taliban compromised the 2020 Doha Agreement. Moreover, al-Zawahiri was reportedly killed in the house of Taliban Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, whose ties with al-Qaeda have been well-documented since the 1980s. It is significant to emphasise the importance of the Haqqani network, as it is one of the most powerful and influential militant groups in the region. A UN-designated terrorist group with 3.000-10.000 fighters, the Haqqani network operates along the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan and mediates between the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

SECURITY LANDSCAPE

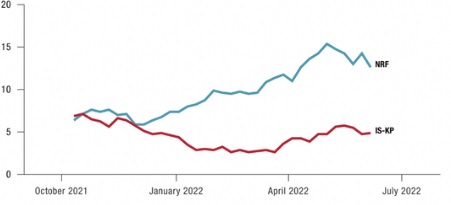

More than one year after Kabul’s fall and the withdrawal of all troops from the country, the Taliban have regained full territorial control. Anti-Taliban demonstrations, especially women-led ones, rose considerably in the first months of the Taliban rule, resulting in an initial escalation of violence. Two main armed groups are battling against the Taliban since the August takeover: the National Resistance Front (NRF) led by A. Massoud and A. Saleh, and the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP). The former is an anti-Taliban resistance group based inside the Panjshir Valley, consisting of at least 8.000 fighters, and largely operating in the northeast of Afghanistan. The latter, instead, was formed in 2015 to overthrow the Pakistani regime and is an Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’s (ISIS) Afghanistan affiliate active in Nangarhar and Kabul provinces. ISKP is also deemed to be the most capable and ambitious terrorist group in Afghanistan (CRS, 2022), in fact, it is responsible for the suicide bombing in Kabul’s airport on August 26, 2021, which caused 170 casualties, resulting in the deadliest terrorist attack in Afghanistan since 2007. The official number of ISKP fighters is unknown, but the killing of al-Zawahiri increased recruits. After the Taliban takeover, the level of violence decreased, but the ISKP launched more attacks due to the chaotic status quo and a tactical shift inside the movement that caused decentralisation and an increase in urban warfare. In particular, the ISKP targeted violence against civilians, mainly Shiites.

However, the NRF has been the most active opposition group to the Taliban since early 2022, conducting more than a dozen of attacks per week. Although NRF fighters are mainly based in the mountains of Panjshir, they have failed to hold a single district there, where armed activity is on the rise since the end of last year.

A third source of violence in the country is dictated by the so-called Pakistani Taliban, or Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a Pashtun militant group holding close ties to the Taliban. The TTP is the actor behind cross-border attacks with Pakistan and has gained operational support from the Taliban, who provided them with safe haven since August 2015, when 2.000 TTP members were released from Afghan prisons. Additional foreign terrorist groups and fighters include militant movements of Uzbek, Tajik, and Turkmen, and the Jaish-e Mohammed and Lashkar-e Tayyiba, which assassinated former government officials and work under the Afghan Taliban’s lead. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that in a changing security landscape, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan holds intra-Taliban fractures, that are significant both to understanding the polycentric identity of the movement and its internal power struggles. A major division is evidenced by the Haqqani network – the Sunni movement extremely close to al-Qaeda – and its rival group led by Mullah Baradar.

THE EU’S ROLE IN AFGHANISTAN

Although the undisputed major contributor in Afghanistan was the US government, the EU response was immediate and targeted different sectors, including military, diplomacy, humanitarian and social policy, politics, and economics. Already in 2001, the European General Affairs and External Relations Council (GAERC) affirmed that the Union would focus primarily on humanitarian aid, and the term reconstruction was added as a requirement (GAERC, 2002). For instance, the EU became a member of the Afghanistan Reconstruction Steering Group (ARSG). In terms of monetary aid, since 2002, the EU has provided Afghanistan with €16 billion between 2001 and 2021, of which €4 billion for development aid and €1.4 billion for humanitarian aid (European Commission, 2022). In 2020, during the Afghanistan Conference in Geneva, the EU allocated €1.2 billion in financial aid to the country for the 2021-2025 period for the Afghan-led peace process (ibidem). In light of the latest developments, the Union assigned more than €200 million and €115 million in humanitarian aid to Afghanistan in 2021 and 2022 respectively. Nevertheless, what truly shaped the EU’s position in Afghanistan in the past two decades was the profound sense of solidarity towards the American government following 9/11. The EU followed the US lead from the beginning, but whilst the Americans were mostly focused on their stabilisation and counterterrorism agendas, the Europeans did not have a unique position and the Member States hampered the realisation of such by following operationally separate and different mandates in Afghanistan. Member States such as Britain, France, and Germany reinforced their cohesion with the US at the expense of a common response from the EU, which resulted in what Political Advisor to the EU Special Envoy to Afghanistan, E. Gross, called a “mini-lateralism” (The Europeanisation of National Foreign Policy, 2009). Although there was an evident lack of internal coherence among EU Member States, they all channelled funding to centralised nation-building efforts. However, this resulted in the underdevelopment of Afghanistan’s rural areas and a lack of empowerment of local voices.

As the EU focused on a top-down and elite-centric process of democratisation, corruption increased, signalling an evident discrepancy between the EU funding and the reality on the ground. This was also confirmed by S. Pontecorvo, NATO’s last Senior Civilian Representative (SCR) for Afghanistan and former Italian Ambassador to Pakistan, who expressed his views on the rampant corruption in Afghanistan in an interview with the author on October 21, 2022. Ambassador Pontecorvo acknowledged that the Taliban inherited an already weak and corrupt state, in which the political errors of Western nations worsened the net endemic corruption. The high degree of corruption that spread across the country in the last twenty years paved the way for the Taliban to start massive campaigns of recruitment whilst Western actors were still active on the ground. Such campaigns specifically targeted the youth, who did not trust the government and consequently were easily recruited into the movement. Together with the Taliban’s ties to the powerful local warlords, the movement continued to grow parallel to the failing missions of nation-building on the ground. The EU humanitarian missions over the last two decades overlooked the strong patronage networks that matured during the Afghan civil war and the last decade. In this way, European and American aid programs easily benefitted the top-level local officials who pursued their self-interest rather than trying to reconstruct their country, thereby deteriorating local trust in the rule of law. Therefore, one of the core challenges for the EU in Afghanistan was an embedded lack of trust for political authorities in the country, which was unconsciously exacerbated by EU aid to the country, and also got translated into social and economic fragmentation, and poor governance. The major error, in this case, was not considering the relevance of corruption, the power of warlords and the possible connection with the Taliban and the Afghan social context illo tempore, whilst funding missions that largely failed.

THE MAJOR ABSENCE OF A UNIQUE EU RESPONSE

Afghanistan’s nation-building operation has been a complex and multifaceted task since the beginning. However, if handled suitably, errors could have been avoided. The idea of exporting democratisation in the case of Afghanistan, which falls under the principles of the Bush Doctrine, was initiated after the successful vindication of the 9/11 attacks. However, without a strict and, most importantly, common agenda and monitoring mechanism, democracy could not stay for long in Afghanistan. The EU never had a major role in Afghanistan, but it is equally responsible for the failure of nation-building, as it fostered an overly superficial strategy of democracy that was not shared by all the Member States. This raises the critical question of strategic autonomy. What would the EU have done if it had been more strategic and autonomous in the security and defence field? Although it is hard to predict what would have happened if there had been a “Europeanisation” of the Afghan response, one thing is certain, and it refers to the words of the EU High Representative/Vice-President (HR/VP) Josep Borrell after the withdrawal of all troops from Afghanistan last summer: “We have to analyse how the EU can further deploy capabilities and positively influence international relations to defend its interests. Our EU strategic autonomy remains at the top of our agenda”, adding that“Afghanistan has shown that the deficiency in our strategic autonomy comes with a price”. The EU was caught off guard when the withdrawal of troops began, thereby leading the Union to completely rely on the US at the moment of evacuation. In addition, the EU already had the possibility to deploy EU battlegroups, although this did not occur as it would have required additional bureaucratic and financial hurdles.

Undoubtedly, the failure in Afghanistan has boosted the pressure on EU members to keep their protectionist behaviours away from the common good of the Union and third countries where the latter is actively participating either militarily or politically, economically, and socially. Henceforth, the only way forward to overcome the EU’s shortcomings in autonomy is to leverage the Member States and stimulate their willingness to jointly act and collaborate. Building on the March 2022 Strategic Compass, through the EU Rapid Deployment Capacity, 5.000 troops will be fully operational to act from 2025. Although this number is still low, bearing in mind what befell in Afghanistan, this could be a start for EU members to strengthen common defence and security capabilities through the European Defence Fund (EDF).

The military operations that Afghanistan witnessed on its territory over the past two decades should have been only a part, albeit an important one of the nation-building. Instead, the military involvement and security questions became everything for the West. On the one hand, the Americans were actively searching for a way to vindicate the 9/11 attacks, but even later, their security agenda prevailed on the one of democratisation. On the other hand, the EU diligently followed the US and NATO, and without a strong and unique front, it could not do otherwise. To avoid the same repercussions in the future, the EU should achieve a certain degree of strategic autonomy in the defence and security industry. This does not want to imply cutting ties with the American government or NATO at large but creating a solid infrastructure with autonomous defence capabilities that could be deployed in case of need without further dependencies.

ADDITIONAL ERRORS AND FUTURE STEPS

Whilst the EU remains fully dedicated to the Afghan people and their safety, stability, prosperity, and well-being, this will compel an inclusive and unified political process toward the participation of Afghan men and women in politics. Monetary aid to Afghanistan should not only target humanitarian operations, as to do so would repeat the errors of the current status quo, which have proved ineffective. Action should be taken to fully support the sector of agriculture, as suggested by Ambassador Pontecorvo as well. More than 70% of Afghans live in rural areas and their incomes are dependent on agriculture. Additionally, most women in Afghanistan are involved in farming and other agriculture-related activities, thereby making this sector essential for the development of skilled women and girls. More than just a paragraph should be devoted to the strength and the role of Afghan women in recent developments in Afghanistan. At the time of writing, Afghan women are persistently gathering in the streets of Kabul and protesting against the lack of formal jobs and access to education. However, the Taliban respond to these demonstrations with violence, beating protesters and unlawfully detaining them as has occurred in the past few months. As the opposition forces are increasing, and women have a strong role in this, Western governments should engage with the Taliban and pressure them to comply with their country’s obligations under international law.

The major error of the West was not the failure of nation-building, instead, no one understood the reality of Afghanistan. First, the Taliban is a polycentric movement, and as such, they could never agree on being managed by a unique voice, as the West wrongly asserted. Second, the Bush Doctrine, whereby a new democratic state would have been created, was put in place thinking that, at the beginning of the 2000s, no state was present or functioning in Afghanistan. Instead, a parallel authority composed of local Pashtuns has always been there and matured in the last twenty years.

CONCLUSION

Through this analysis, it is clear that the errors made on the ground in Afghanistan are part of a bigger picture. The systematic failures committed by Western powers ended in the failure of nation-building and the malfunction of the Bush Doctrine. The latter, as shown in this paper, can only succeed when a state is built from scratch, otherwise, as it has occurred in Afghanistan, parallel local structures will mature over time thanks to endemic corruption and third countries’ aid, i.e., Pakistan in this case. The EU’s lack of unity, full dependence on the US and NATO, and reliance on the latter’s complete military involvement resulted in overly superficial missions. The behaviour of the Union, insofar as EU Member States were divided without a common agenda, hindered the process of human development of Afghan society, whose Human Development Index (HDI) did not increase as expected with the EU actions on the ground. Not only did the EU operations lack cohesion among the Member States, but they also failed to target the right sectors, unconsciously funding patronage

networks that gained power in the final years before the withdrawal.

Undoubtedly, what happened in Kabul is a failure of the international community. Brussels has learnt it has to show a more cohesive front when pursuing missions abroad, and attention to the strategic autonomy concept is more evident than twenty years ago. Firstly, in the 2022 Strategic Compass, the Union has agreed to increase its battlegroups, which would have been valuable during the evacuation of military and civilian personnel from Afghanistan and secondly, EU members are engaged in several joint projects under the umbrella of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). Nonetheless, European strategic autonomy is still a work in progress, and a lot needs to get done to fully achieve it.

In conclusion, as Afghanistan’s security, social, and financial landscapes are persistently fluctuating under the Taliban’s lead, it is challenging to foresee what is coming next. What is certain is that the EU has learnt to holistically understand the context in which it has to act before funding missions abroad. The EU is still committed to humanitarian operations in the country, but without addressing corruption, social fragmentation, and proper engagement with the Taliban, little will be achieved. In particular, with Europe being indirectly involved on the Ukrainian front, attention cannot deviate from Afghanistan any longer, as illicit migration and drug trafficking are on the rise. Russia is unquestionably a significant player in this arena, given its special relationship with the Taliban, making Western powers cannot overlook Moscow’s interference in Afghanistan and the region overall.